Abortion has been available throughout Germany since the 1970s but the number of doctors carrying out the procedure is now in decline. Jessica Bateman meets students and young doctors who want to fill the gap.

The woman at the family planning clinic looked at Teresa Bauer and her friend sternly. "And what are you studying?" she asked the friend, who had just found out she was pregnant, and wanted an abortion.

"Cultural studies," she replied.

"Ahhh, so you're living a colourful lifestyle?" came the woman's retort.

Bauer sat still, hiding her rage.

Stressed-out by the discovery of her accidental pregnancy, Bauer's friend had asked her to book the appointments needed to arrange an abortion.

It wasn't just a case of calling her friend's GP to arrange a time for her to request a termination.

First she needed to arrange a counselling appointment, which is designed to "protect unborn life", as German law puts it, and discourage a woman from going ahead with the procedure. Some of the clinics providing the service are run by churches - Bauer took care to avoid them, fearing that they would be judgemental.

Then she needed to hunt down a doctor who could prescribe pills for an early medical abortion. It became legal last year for doctors to publicise the fact that they provide abortions but they cannot indicate what kinds of service they provide, so Bauer had to call medical practices one by one.

"Berlin is a liberal city, so I thought it would be easier than it was," she says.

"Even when we went to get the pill, the doctor's assistant kept asking, 'Are you really sure?' Seeing what my friend had to go through, and how she was treated, made me so angry that I decided to do something about it."

Bauer was a third-year medical student at the time, so a few days later she emailed Medical Students for Choice Berlin, run by students at her university, telling them she wanted to start volunteering. She now works with them, campaigning for improved training on abortion for medical students, and raising awareness of the obstacles that people seeking an abortion may face.

Although Germany is widely perceived as a liberal country, its reproductive laws are surprisingly restrictive. Abortion isn't actually legal - it's just unpunished up to 12 weeks from conception, providing the woman has undergone the counselling session, followed by a waiting period of three days.

For this reason abortion hasn't been taught at medical schools, and there is a shortage of doctors performing the procedure as a result.

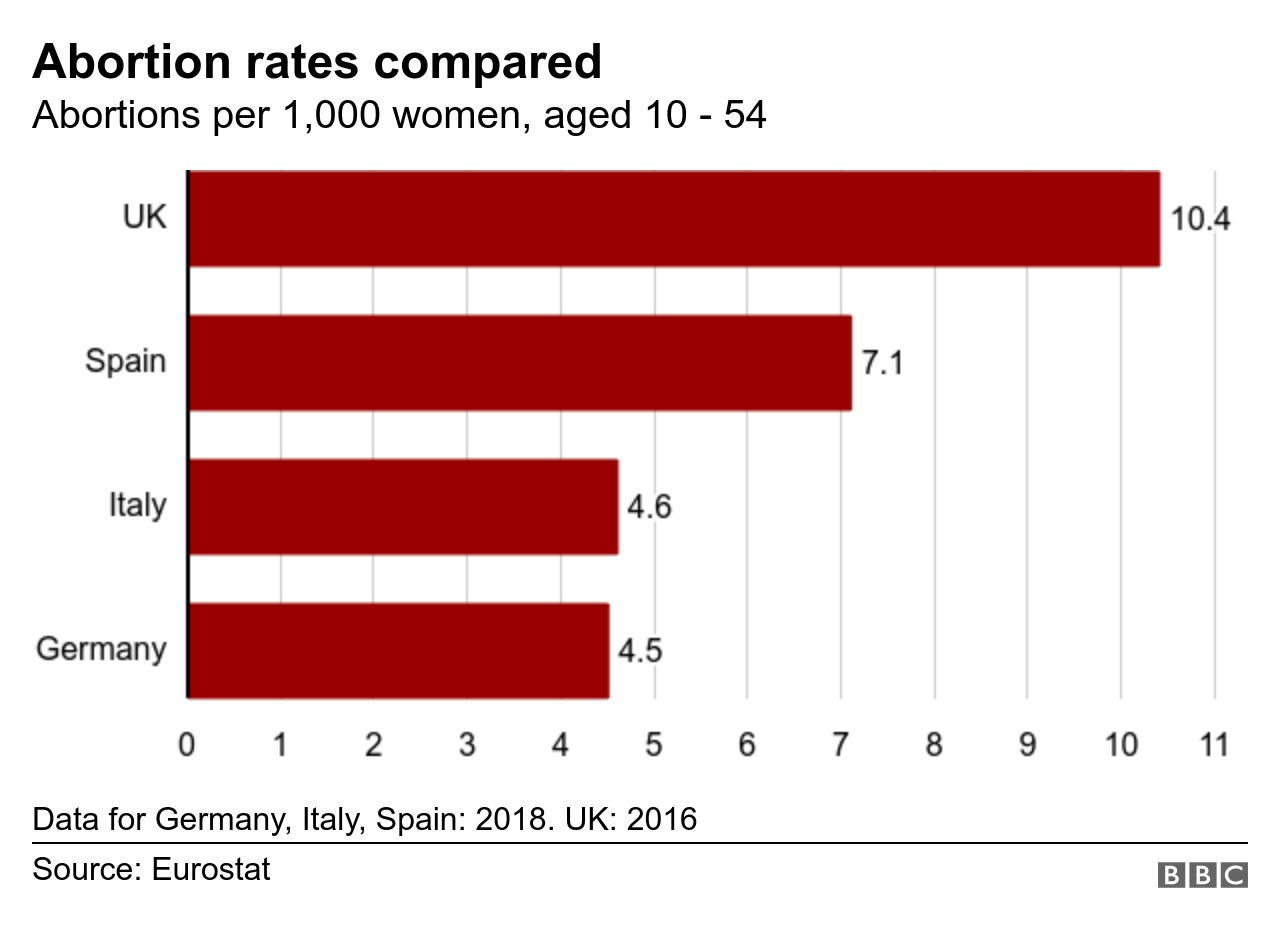

In some parts of Germany women have to travel long distances to reach a clinic where abortions are carried out. In 2018 more than 1,000 crossed into the Netherlands, where the process is simpler and the time limit is 22 weeks. Some doctors also commute from Belgium and the Netherlands to carry out abortions in northern German cities such as Bremen and Münster.

Germany's criminal code

GETTY IMAGES

- Section 218 declares abortion illegal

- 218a provides "exception to liability" for abortions carried out in the first trimester, or later in cases of medical necessity - subject to counselling and a three-day wait

- 219a bans advertising of abortion services, though since 2019 it has been possible for doctors to publicise the fact that they provide abortions, as long as they give no further details

Medical Students for Choice Berlin is trying to address the difficulties faced by women seeking an abortion by holding papaya workshops, where the procedure is carried out on the tropical fruit. Its size makes a handy stand-in for a human uterus, and its seeds are vacuumed out to demonstrate how the foetus may be removed. The idea is to get students in touch with the topic, and to encourage them to pursue specialist training after finishing their undergraduate course.

The group was founded in 2015 by Alicia Baier, who says she only found out about the difficulties faced by women seeking an abortion by chance, at a conference during her fourth year of medical studies.

"It's a taboo subject and no-one talks about it, so most people don't know about the access problems until they actually need to get an abortion themselves," she says.

She then discovered that most doctors performing abortions in Germany are in their 60s and 70s and are due to retire soon. "They're the generation that experienced the past fights for women's rights," she says. "They became politicised. But the younger generations never learnt how to do it."

Baier got in touch with a US group called Medical Students for Choice, which explained that papayas can be used in demonstrations. "They even posted the tools for us to use," she adds. A lecturer then connected her with some gynaecologists who could host the workshops. "They said to me, 'We've been waiting so long for students like you!'"

In Lower Bavaria, a region with a population of 1.2 million bordering Austria and the Czech Republic, the last remaining gynaecologist performing abortions came out of retirement five years ago, as no other doctor in the 80% Catholic region would agree to take over from him. But 72-year-old Michael Spandau stopped again completely in March, because his age put him at risk during the Covid-19 outbreak.

"Women have to travel to Munich or Regensburg, 130km (80 miles) away," says Thoralf Fricke from the local branch of family planning charity Pro Familia, situated in the centre of the picturesque, pastel-painted city of Passau. "If you don't have a car, you need to travel by train. This is expensive. If you live in a rural area, it takes three hours each way. And it is a risk to your health - this operation isn't like having a tooth out. You could have complications such as blood pressure problems."

There is also a large population of refugee women in the region, who are often housed in rural areas while they wait for their asylum applications to be processed. They tend not to have support networks that can help them find lifts or overnight accommodation.

JESSICA BATEMAN

Rose, who is from Nigeria and lives a 40-minute bus ride outside of Passau, needed an abortion last December. "My daughter is six months old and I told my boyfriend, I cannot cope with another child so soon," she explains. Luckily she was able to spend the night after the procedure at the home of a pro-choice activist, Lea. "I was feeling very dizzy afterwards," she recalls. "I was so lucky I was with Lea because she supported me as I walked. If I had to get the bus then maybe I would have collapsed."

The German Association of Gynaecologists told the BBC: "In Germany, it is the responsibility of the federal states to give pregnant women in crisis situations sufficient advice and assistance. The law §12(1) states that no-one is obliged to participate in an abortion. The only exception is when the life of the mother is threatened.

"Gynaecologists and medical staff are free to decide following their religion and their ethics if they want to perform or to deny abortions. No-one must be forced. In regions where Catholicism is predominant, fewer physicians and nurses are to be found. Then, women must take longer distances into account."

The hospital in Passau said the city hall had taken the decision in 2007 that abortions would only be carried out at the hospital in emergencies.

Abortion has a long and complex history in Germany. In the Nazi era, performing an abortion on a white German woman was a capital offence unless the foetus was deformed or disabled; by contrast, women from other ethnic groups were encouraged to undergo abortions. In later years, communist East Germany had more liberal laws, but the West's more conservative stance became standard after reunification in 1990.

The law banning advertisement of services, 219a, which was established in the Nazi era, has recently been used by anti-abortion activists to bring legal action against doctors around the country. Thoralf Fricke says he has had an increase in hate mail over the past two years, with activists sending him death threats and foetus dolls. Before the pandemic protesters had begun standing outside the Pro Familia clinic, where women go for pre-abortion counselling.

"Some women didn't arrive for their appointments," he says. "We think they were intimidated."

GETTY IMAGES

But the pro-choice movement is growing stronger too. As a result of Medical Students for Choice's campaign, the Charité university hospital in Berlin last year added abortion to its curriculum for the first time ever, as did Münster university. If social distancing allows, the group plans to hold a training weekend with medical students from all over the country in Berlin this autumn.

Alicia Baier has now finished her studies and is training at a doctor's practice that provides abortions. Here she sees first hand how the lack of access impacts women. "One doctor made a woman unnecessarily wait an extra week, which pushed her over the limit for a medical abortion [using pills]," she explains. After nine weeks, the only option is a surgical abortion using the vacuum technique.

Tragically, Baier also came into contact with one 19-year-old trapped in an abusive situation, who attempted a home abortion for lack of information about where to get a safe one. Her uterus had to be removed.

Even though more students are now learning the procedure, Baier says, their age means there will still be a gap in services for the foreseeable future.

"It will take a number of years before we can run our own practices," she says. "And before that, as the current doctors retire, we're going to have big problems."

Papaya workshop photographs taken by M Römer, A Kolandt and N Kutsche

You may also be interested in:

For a couple of weeks every month, Lucie seemed to become a different person - one suffering from countless mental and physical problems - and she couldn't understand why. She spent years looking for a doctor who could provide an answer, and it took a hysterectomy at the age of 28 to cure her.

0 Comments